About Penn’s Picks:

From obscure underground gems to timeless classics (and everything in between), Hit Songs Deconstructed Co-Founder, David Penn, gives his personal picks showcasing songs and artists that helped shape music history.

In addition to strong melodies, hooks, lyrics and arrangements, a strategic energy flow is integral to keeping a song interesting and heightening its emotional connection with the listener.

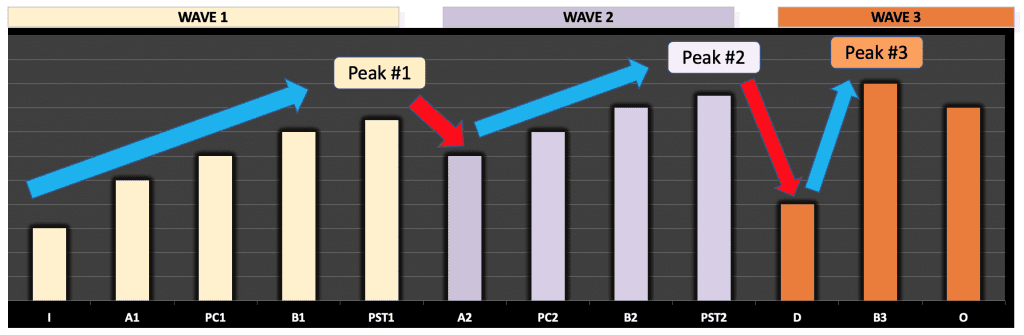

In today’s pop music scene, the most common energy flow is an energy build from the intro through the first chorus or post-chorus, a dip down in the second verse followed by a build back up through the second chorus or post-chorus, another dip in the bridge, and a final ramp up to an energy peak in the last chorus. This is then either maintained or wound down to a low-energy conclusion in the outro. Essentially, you can think of this energy flow as a roller coaster ride with peaks and valleys; some songs have greater peaks and valleys while others may have a more linear flow with less dynamic range, but most hit pop songs still follow this same roller coaster-like shape.

This particular energy flow is highly effective for a number of reasons. The first is that because it’s used so often, it creates familiarity for listeners and helps them connect with the song more easily. Furthermore, it also keeps listeners engaged from start to finish and allows higher energy sections like the chorus to further stand out and be remembered.

Some songs, however, opt for something a bit more unique. One energy flow variation used by some of the greatest artists of all time is the use of a continuous build throughout an entire song or within one particular section to bring the song to a huge, tension-filled climax. While this method, which I’ve dubbed “the art of the build,” is more common in the music of yesterday than today, it has been used in both notable hits and underground classics alike across styles and genres.

In this Penn’s Picks, I’ve selected some of my favorite songs from yesterday and today that use “the art of the build” to great avail across an array of genres, including soul, gospel, hip hop, garage, prog, jazz, and rock.

Full Spotify playlist available at end of article

Written by Will Holt back in 1956 and performed by an array of artists over the years, Sinnerman had already been around for quite a while before Nina Simone’s 1965 recording turned it into a timeless classic. Clocking in at over 10 minutes in length, this gospel-influenced tour-de-force builds lyrically, vocally and musically across the first three-and-a-half minutes, culminating in a rousing call and response between the band and Simone’s triumphant “power!” And given the song’s religious, panic-driven lyrics, this was certainly well-warranted to give the song the emotional punch it needed.

Before Bob Seger achieved mass success in the 1970s and 1980s both as a solo artist and with his famed Silver Bullet Band, there was the Bob Seger System. Active from 1968 to 1970, the band is known in part for their performance of one of the most harrowing tracks of the time period, 1969’s 2+2=?. This garage/psych nugget is a staunch protest against the Vietnam War that builds both vocally and musically through its 2:45 run, layering in elements to bring intensity to a feverish peak in support of its distressing lyrics.

Though it was originally written back in 1932 and recorded by an array of artists including crooner Bing Crosby, Try a Little Tenderness didn’t reach icon status until soul artist Otis Redding and his backing band Booker T. & The M.G.’s put their stamp on it in 1966. The song begins as a sweet soul ballad but gradually adds more and more elements to the mix as it progresses, culminating in a rousing crescendo by the end. While this is evident in the song’s studio version, its true power was revealed in a live setting, where Otis would whip the audience into a “revival”-like frenzy over the course of numerous encores.

Before there was David Gilmore, there was Syd Barrett. The driving force behind Pink Floyd’s iconic psychedelic first album The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn, Barrett’s creative genius put Floyd on the map and inspired countless artists and bands, including Paul McCartney, David Bowie, Marc Bolan, The Flaming Lips and Robyn Hitchcock, to name just a few. Prior to being sidelined due to overindulgence, Barrett recorded two final tracks with the band in late 1967/early 1968, one of which was Scream Thy Last Scream. Their label, however, deemed it too “out there” for release, and shelved it, dooming it to see the light of day only through bootlegs and as part of an official Floyd compilation in 2016.

At the core of the song’s twisted brilliance is an instrumental break that lasts for around one minute and thirty seconds. The section’s momentum and intensity gradually build around a “wah wah” organ solo as the song’s tempo progressively speeds up, pushing it into a screaming frenzy that does justice to the song’s title.

While the Beatles were never strangers to the “heavier” side (i.e. 1966’s trippy, dense and driving Tomorrow Never Knows and 1968’s metal-esque Helter Skelter), it wasn’t until 1969’s I Want You (She’s So Heavy) that The Beatles added overt darkness to the equation. While the verses lean more toward the blues end of the spectrum, the intro and choruses feature a foreboding riff that no doubt inspired many metal bands to come and laid the groundwork for the doomy Black Sabbath the next year. The riff reaches its full power in the outro where it repeats for a full three minutes as additional instrumental layers are progressively added in, taking the song to a grand climax before abruptly cutting off at the end. When listening to the full album, this dark, heavy build and abrupt cutoff make for an impactful segue into the much brighter and lighter Here Comes The Sun.

Radiohead’s 1997 album OK Computer is characterized by its experimental production techniques, atmospheric electro style and moody lyrics, causing many to – much like Floyd’s Scream Thy Last Scream – write the album off as uncommercial. However, to pre-release critics’ dismay, the album was almost universally adored for its ambitious, contrasting styles and poignant, emotional lyrics.

One of the most emotive songs on the album is Exit Music (For A Film), which was inspired by the depressing narrative of Romeo and Juliet. The song kicks off in a state of calm with acoustic guitar and subdued vocals before progressively growing into an angry rock groove at its climax, symbolizing the escalation of Romeo and Juliet’s affair to both lovers dying. The song then releases back into a calm, melancholy outro accompanied by the cryptic repeated phrase, “we hope that you choke, that you choke.”

Popular jazz standard Afro Blue has been recorded countless times over, each version with its own unique take. One of the most well-known – and most intense – of the lot is John Coltrane’s 1965 take recorded live at the Half Note. The song begins with the melody performed by Coltrane on soprano saxophone before launching into a solo by pianist McCoy Tyner. As the three-minute solo continues, McCoy progressively heightens intensity along with rapid fire accompaniment from drummer Elvin Jones and driving bass lines from Jimmy Garrison before releasing into a screaming solo by Coltrane to ride the song out on an emotionally intense high.

An iconic track from The Doors’ 1968 album Waiting For The Sun (and originally a component of Morrison’s epic Celebration of the Lizard), Not To Touch The Earth is a dark, primal masterpiece that showed what the state of society really like was following 1967’s Summer of Love. Over the course of the song, the band shifts into a more driving, pummeling state with each passing verse, eventually reaching a feverish pitch at the three-and-a-half-minute mark before crashing all down at the end. This version of the song, which is taken from a 1970 performance and featured on their Absolutely Live album, shows The Doors at the peak of their powers.

Starless, a notable track from King Crimson’s Red album, begins as a mellow, flowing, mellotron-driven prog song. However, things abruptly change around the four-and-a-half-minute mark, where the song breaks down to Wetton’s ominous bass line and Fripp’s simple, monotone guitar pattern. From this point on, the same motif continues, gradually rising in pitch, density and intensity before briefly breaking down once again to set up the frenzied climax around 9:00 (studio version) / 8:30 (live video).

While builds such as those above are exceptionally rare in today’s mainstream music scene, there are always bound to be exceptions. The most recent example can be found in the Post Malone, Ozzy Osbourne and Travis Scott collaboration Take What You Want, which pulls both from popular genres like pop and hip hop as well as the less common metal genre.

The majority of the song follows a fairly common energy flow, which creates mainstream familiarity and helps to keep listeners engaged. However, at the three-minute mark, the song takes an unexpected turn and shifts into a screaming guitar solo over a single driving rhythm guitar. As the solo progresses, both trap and rock drums are added in along with vocals from all three artists, joining the song’s diverse influences together under one roof and taking its energy to a tension-filled peak. This emotional, screaming build also jibes with the song’s lyrics, which focus on an angry man who has been taken advantage of by his lover.

Penn’s Picks: The Art of the Build Spotify Playlist